Are Ponds Freshwater Or Saltwater

A man made swimming at sunset in Montgomery County, Ohio.

Stereoscopic epitome of a pond in Central City Park, Macon, GA, circa 1877.

A pond is an area filled with h2o, either natural or bogus, that is smaller than a lake.[1] Defining them to be less than v hectares (12 acres) in area, less than 5 meters (sixteen ft) deep, and with less than thirty% emergent vegetation helps in distinguishing their ecology from that of lakes and wetlands.[2] [iii] : 460 Ponds can exist created by a wide variety of natural processes (east.g. on floodplains as cutoff river channels, by glacial processes, past peatland formation, in coastal dune systems, by beavers), or they can only be isolated depressions (such as a kettle hole, vernal puddle, prairie pothole, or simply natural undulations in undrained land) filled by runoff, groundwater, or precipitation, or all 3 of these.[4] They tin exist farther divided into four zones: vegetation zone, open water, lesser mud and surface film.[3] : 160–163 The size and depth of ponds ofttimes varies greatly with the time of year; many ponds are produced by bound flooding from rivers. Ponds may be freshwater or brackish in nature. 'Ponds' with saltwater, with a direct connexion to the sea that maintains full salinity, would normally exist regarded every bit office of the marine surround because they would not support fresh or stagnant water organisms, then not really inside the realm of freshwater science.

Ponds are usually by definition quite shallow water bodies with varying abundances of aquatic plants and animals. Depth, seasonal water level variations, nutrients fluxes, amount of light reaching the ponds, the shape, the presence of visiting large mammals, the composition of any fish communities and salinity can all affect the types of institute and animal communities present.[5] Nutrient webs are based both on gratuitous-floating algae and upon aquatic plants. At that place is usually a diverse array of aquatic life, with a few examples including algae, snails, fish, beetles, h2o bugs, frogs, turtles, otters and muskrats. Acme predators may include large fish, herons, or alligators. Since fish are a major predator upon amphibian larvae, ponds that dry out upwardly each twelvemonth, thereby killing resident fish, provide important refugia for amphibian convenance.[5] Ponds that dry out up completely each year are oft known every bit vernal pools. Some ponds are produced past animal activeness, including alligator holes and beaver ponds, and these add important diversity to landscapes.[5]

Ponds are frequently manmade or expanded beyond their original depths and bounds by anthropogenic causes. Apart from their role as highly biodiverse, fundamentally natural, freshwater ecosystems ponds have had, and still have, many uses, including providing water for agriculture, livestock and communities, aiding in habitat restoration, serving as convenance grounds for local and migrating species, decorative components of landscape architecture, alluvion command basins, general urbanization, interception basins for pollutants and sources and sinks of greenhouse gases.

Classification [edit]

The technical distinction between a pond and a lake has not been universally standardized. Limnologists and freshwater biologists accept proposed formal definitions for swimming, in part to include 'bodies of water where light penetrates to the bottom of the waterbody,' 'bodies of h2o shallow enough for rooted water plants to grow throughout,' and 'bodies of h2o which lack moving ridge activeness on the shoreline.' Each of these definitions are difficult to measure out or verify in exercise and are of express practical employ, and are mostly not now used. Accordingly, some organizations and researchers have settled on technical definitions of swimming and lake that rely on size lonely.[half dozen]

Some regions of the The states ascertain a pond as a body of h2o with a surface area of less than 10 acres (4.0 ha). Minnesota, known equally the "land of 10,000 lakes", is commonly said to distinguish lakes from ponds, bogs and other water features past this definition,[vii] but also says that a lake is distinguished primarily past moving ridge action reaching the shore.[eight] Even among organizations and researchers who distinguish lakes from ponds past size alone, there is no universally recognized standard for the maximum size of a pond. The international Ramsar wetland convention sets the upper limit for swimming size as 8 hectares (lxxx,000 chiliad2; twenty acres).[9] Researchers for the British charity Pond Conservation (now called Freshwater Habitats Trust) accept defined a pond to be 'a human being-made or natural waterbody that is between 1 m2(0.00010 hectares; 0.00025 acres) and 20,000 m2 (2.0 hectares; iv.9 acres) in surface area, which holds water for four months of the year or more.' Other European biologists have set the upper size limit at v hectares (50,000 m2; 12 acres).[x]

In Due north America, even larger bodies of water have been called ponds; for example, Crystal Lake at 33 acres (130,000 kii; 13 ha), Walden Swimming in Concord, Massachusetts at 61 acres (250,000 m2; 25 ha), and nearby Spot Pond at 340 acres (140 ha). At that place are numerous examples in other states, where bodies of h2o less than ten acres (40,000 m2; 4.0 ha) are existence called lakes. As the case of Crystal Lake shows, marketing purposes tin sometimes exist the driving factor behind the categorization.[eleven]

In practise, a sea is called a pond or a lake on an private footing, as conventions alter from place to place and over time. In origin, a pond is a variant form of the give-and-take pound, meaning a circumscribed enclosure.[12] In earlier times, ponds were artificial and utilitarian, as stew ponds, mill ponds then on. The significance of this feature seems, in some cases, to accept been lost when the discussion was carried abroad with emigrants. However, some parts of New England contain "ponds" that are really the size of a small lake when compared to other countries. In the United States, natural pools are often called ponds. Ponds for a specific purpose keep the adjective, such as "stock pond", used for watering livestock. The term is also used for temporary accumulation of water from surface runoff (ponded h2o).

There are various regional names for naturally occurring ponds. In Scotland, one of the terms is lochan, which may also apply to a big body of water such equally a lake. In the South Western parts of North American, lakes or ponds that are temporary and often dried up for almost parts of the year are called playas.[thirteen] These playas are simply shallow depressions in dry areas that may just fill with h2o on certain occasion like backlog local drainage, groundwater seeping, or rain.

Formation [edit]

Pond formation through seeping groundwater in South Tufa, California

Any low in the ground which collects and retains a sufficient amount of water can exist considered a pond, and such, can be formed by a diversity of geological, ecological, and human terraforming events.

Ornamental swimming with waterfall in Niagara Falls Stone Garden

Natural ponds are those caused by environmental occurrences. These tin can vary from glacial, volcanic, fluvial, or even tectonic events. Since the Pleistocene epoch, glacial processes have created nearly of the Northern hemispheric ponds; an case is the Prairie Pothole Region of North America.[fourteen] [fifteen] When glaciers retreat, they may leave backside uneven ground due to bedrock elastic rebound and sediment outwash plains.[16] These areas may develop depressions that tin can fill up with excess precipitation or seeping ground water, forming a modest pond. Kettle lakes and ponds are formed when ice breaks off from a larger glacier, is somewhen buried by the surrounding glacial till, and over time melts.[17] Orogenies and other tectonic uplifting events accept created some of the oldest lakes and ponds on the globe. These indentions accept the trend to quickly fill up with groundwater if they occur beneath the local water table. Other tectonic rifts or depressions tin fill with atmospheric precipitation, local mount runoff, or be fed by mountain streams.[18] Volcanic activity can too lead to lake and pond formation through collapsed lava tubes or volcanic cones. Natural floodplains along rivers, as well equally landscapes that incorporate many depressions, may experience jump/rainy flavour flooding and snow melt. Temporary or vernal ponds are created this way and are important for convenance fish, insects, and amphibians, particularly in large river systems like the Amazon.[19] Some ponds are solely created by animals species such equally beavers, bison, alligators and other crocodilians through damning and nest excavation respectively.[20] [21] In landscapes with organic soils, local fires can create depressions during periods of drought. These accept the tendency to fill up with pocket-sized amounts of precipitation until normal water levels return, turning these isolated ponds into open water.[22]

Manmade ponds are those created by homo intervention for the sake of the local surround, industrial settings, or for recreational/ornamental utilise.

Uses [edit]

Many ecosystems are linked by water and ponds have been found to concur a greater biodiversity of species than larger freshwater lakes or river systems.[23] As such, ponds are habitats for many varieties of organisms including plants, amphibians, fish, reptiles, waterfowl, insects and even some mammals. Ponds are used for breeding grounds for these species merely as well as shelter and even drinking/feeding locations for other wildlife.[24] [25] Aquaculture practices lean heavily on artificial ponds in order to grow and care for many dissimilar type of fish either for human consumption, research, species conservation or recreational sport.

In agriculture practices, treatment ponds can be created to reduce nutrient runoff from reaching local streams or groundwater storages. Pollutants that enter ponds can often exist mitigated by natural sedimentation and other biological and chemical activities within the water. As such, waste material stabilization ponds are becoming popular low-cost methods for full general wastewater handling. They may besides provide irrigation reservoirs for struggling farms during times of drought.

As urbanization continues to spread, retention ponds are becoming more than common in new housing developments. These ponds reduce the adventure of flooding and erosion damage from backlog storm water runoff in local communities.[26]

Experimental ponds are used to test hypotheses in the fields of ecology science, chemical science, aquatic biology, and limnology.[27]

Some ponds are the life blood of many small villages in arid countries such as those in sub-Saharan Africa where bathing, sanitation, line-fishing, socialization, and rituals are held.[28] In the Indian subcontinent, Hindu temple monks care for sacred ponds used for religious practices and bathing pilgrims akin.[29] In Europe during medieval times, it was typical for many monastery and castles (small-scale, partly self-sufficient communities) to have fish ponds. These are nonetheless common in Europe and in Eastern asia (notably Japan), where koi may exist kept or raised.

In Nepal artificial ponds were essential elements of the ancient drinking water supply organisation. These ponds were fed with rainwater, water coming in through canals, their own springs, or a combination of these sources. They were designed to retain the water, while at the aforementioned fourth dimension letting some water seep away to feed the local aquifers.[thirty]

Pond biodiversity [edit]

Azalea flowers around a still swimming in London'south Richmond Park

A defining characteristic of a swimming is the presence of continuing water which provides habitat for a biological customs commonly referred to as pond life. Because of this, many ponds and lakes comprise large numbers of endemic species that have gone through adaptive radiations to get specialized to their preferred habitat.[xviii] Familiar examples might include h2o lilies and other aquatic plants, frogs, turtles, and fish.

Mutual freshwater fish species include the Big Mouth and Small-scale Rima oris Bass, Catfish, Bluegill, and Sunfish such as the Pumpkinseed Sunfish shown above

Often, the entire margin of the swimming is fringed by wetland, and these wetlands support the aquatic food web, provide shelter for wildlife, and stabilize the shore of the pond. This margin is also known equally the littoral zone and contains much of the photosynthetic algae and plants of this ecosystem called macrophytes. Other photosynthetic organisms such as phytoplankton (suspended algae) and periphytons (organisms including cyanobacteria, detritus, and other microbes) thrive here and stand up as the primary producers of pond food webs.[18] Some grazing animals like geese and muskrats consume the wetland plants directly as a source of nutrient. In many other cases, pond plants volition decay in the water. Many invertebrates and herbivorous zooplankton and so feed on the decaying plants, and these lower trophic level organisms provide food for wetland species including fish, dragonflies, and herons both in the littoral zone and the limnetic zone.[18] The open water limnetic zone may allow algae to abound equally sunlight still penetrates here. These algae may support yet another food web that includes aquatic insects and other modest fish species. A pond, therefore, may have combinations of three different food webs, one based on larger plants, i based upon rust-covered plants, and one based upon algae and their specific upper trophic level consumers and predators.[18] Hence, ponds oft have many different animal species using the wide assortment of food sources though biotic interaction. They, therefore, provide an important source of biological diverseness in landscapes.

Opposite to long continuing ponds are vernal ponds. These ponds dry up for part of the year and are and then called because they are typically at their peak depth in the spring (the meaning of "vernal" comes course the Latin word for bound). Naturally occurring vernal ponds practice not usually have fish, a major higher tropic level consumer, as these ponds oftentimes dry up. The absence of fish is a very important feature of these ponds since it prevents long chained biotic interactions from establishing. Ponds without these competitive predation pressures provides breeding locations and prophylactic havens for endangered or migrating species. Hence, introducing fish to a pond can have seriously detrimental consequences. In some parts of the globe, such as California, the vernal ponds have rare and endangered plant species. On the coastal plain, they provide habitat for endangered frogs such as the Mississippi Gopher Frog.[20]

Oft groups of ponds in a given landscape - then called 'pondscapes' - offer especially high biodiversity benefits compared to unmarried ponds. A grouping of ponds provides a college degree of habitat complication and habitat connectivity.[31] [32]

Stratification [edit]

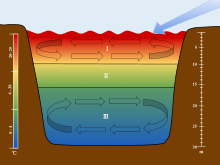

Lakes are stratified into 3 separate sections: I. The Epilimnion II. The Metalimnion Three. The Hypolimnion. The scales are used to associate each section of the stratification to their respective depths and temperatures. The arrow is used to show the movement of wind over the surface of the water which initiates the turnover in the epilimnion and the hypolimnion.

Many ponds undergo a regular yearly procedure in the same matter as larger lakes if they are deep enough and/or protected from the current of air. Abiotic factors such as UV radiation, full general temperature, wind speed, water density, and even size, all have important roles to play when it comes to the seasonal effects on lakes and ponds.[33] Spring overturn, summertime stratification, autumn turnover, and an inverse winter stratification, ponds adjust their stratification or their vertical zonation of temperature due to these influences. These environmental factors affect swimming apportionment and temperature gradients within the water itself producing afar layers; the epilimnion, metalimnion, and hypolimnion.[eighteen]

A pond in wintertime experiencing inverse stratification

Each zone has varied traits that sustain or harm specific organisms and biotic interactions beneath the surface depending on the season. Winter surface ice begins to melt in the Spring. This allows the water column to brainstorm mixing thanks to solar convection and wind velocity. As the pond mixes, an overall constant temperature is reached. As temperatures increase through the summer, thermal stratification takes identify. Summertime stratification allows for the epilimnion to be mixed by winds, keeping a consequent warm temperature throughout this zone. Here, photosynthesis and chief production flourishes. However, those species that need libation water with higher dissolved oxygen concentrations will favor the lower metalimnion or hypolimnion. Air temperature drops as fall approaches and a deep mixing layer occurs. Autumn turnover results in isothermal lakes with high levels of dissolved oxygen as the h2o reaches an boilerplate colder temperature. Finally, wintertime stratification occurs inversely to summertime stratification equally surface ice begins to grade yet once again. This ice cover remains until solar radiation and convection return in the spring.

Due to this abiding alter in vertical zonation, seasonal stratification causes habitats to abound and shrink accordingly. Sure species are bound to these singled-out layers of the water cavalcade where they can thrive and survive with the best efficiency possible.

For more information regarding seasonal thermal stratification of ponds and lakes, please look at "Lake Stratification".

Conservation and direction [edit]

Ponds provide not only ecology values, merely applied benefits to gild. One increasingly crucial benefit that ponds provide is their ability to act every bit greenhouse gas sinks. About natural lakes and ponds are greenhouse gas sources and aid in the flux of these dissolved compounds. However, manmade farm ponds are becoming significant sinks for gas mitigation and the fight against climatic change.[34] These agriculture runoff ponds receive high pH level water from surrounding soils. Highly acidic drainage ponds human activity every bit catalysis for excess CO2 (carbon dioxide) to be converted into forms of carbon that can easily be stored in sediments.[35] When these new drainage ponds are synthetic, concentrations of bacteria that commonly break down dead organic matter, such as algae, are low. As a result, breakdown and release of nitrogen gases from these organic materials such equally N2O does not occur and thus, not added to our temper.[36] This process is also used with regular denitrification in anoxic layer of ponds. Notwithstanding, not all ponds take the power to become sinks for greenhouse gasses. Most ponds feel eutrophication where faced with excessive nutrient input from fertilizers and runoff. This over-nitrifies the pond h2o and results in mass algae blooms and local fish kills.

Some farm ponds are not used for runoff control merely rather for livestock similar cattle or buffalo as watering and bathing holes. Every bit mentioned in the utilise section, ponds are important hotspots for biodiversity. Sometimes this becomes an issue with invasive or introduced species that disrupt pond ecosystem dynamics such as nutrient-web structure, niche partitioning, and guild assignments.[37] This varies from introduced fish species such equally the Mutual Carp that eat native water plants or Northern Snakeheads that assault convenance amphibians, aquatic snails that carry infectious parasites that impale other species, and even rapid spreading aquatic plants like Hydrilla and Duckweed that can restrict water flow and crusade overbank flooding.[37]

Ponds, depending on their orientation and size, tin can spread their wetland habitats into the local riparian zones or watershed boundaries. Gentle slopes of land into ponds provides an area of habitat for wetland plants and moisture meadows to aggrandize beyond the limitation of the pond.[38] Yet, the construction of retaining walls, lawns, and other urbanized developments can severely degrade the range of pond habitats and the longevity of the pond itself. Roads and highways act in the same manor, but they likewise interfere with amphibians and turtles that drift to and from ponds as part of their annual convenance cycle and should exist kept as far away from established ponds as possible.[39] Because of these factors, gently sloping shorelines with wide expanses of wetland plants not merely provide the all-time conditions for wildlife, merely they help protect h2o quality from sources in the surrounding landscapes. It is also beneficial to allow water levels to fall each year during drier periods in order to re-establish these gentile shorelines.[39]

In landscapes where ponds are artificially synthetic, they are done so to provide wildlife viewing and conservation opportunities, to treat wastewater, for sequestration and pollution containment, or for only aesthetic purposes. For natural pond conservation and development, one way to stimulate this is with general stream and river restoration. Many pocket-size rivers and streams feed into or from local ponds inside the aforementioned watershed. When these rivers and streams flood and begin to meander, large numbers of natural ponds, including vernal pools and wetlands, develop.[40]

Examples [edit]

Some notable ponds are:

- Big Pond, Nova Scotia, Canada

- Christian Pond, Wyoming, United States

- Walden Swimming, Massachusetts, United states, associated with Henry David Thoreau

- Hampstead Ponds, London

- Kuttam Pokuna, Medieval bogus pond in Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka

- Rani Pokhari, 17th-century artificial pond in Kathmandu, Nepal

- Rožmberk Pond, Czechia

Run across also [edit]

- Cypress dome – Swamp dominated past swimming or bald cypress

- Handling pond

- Water garden – Garden with water every bit a main feature

References [edit]

- ^ STANLEY, E. Thou. (1 June 1975). "The Merriam-Webster Dictionary – The Oxford Illustrated Dictionary". Notes and Queries. 22 (six): 242–243. doi:10.1093/nq/22-6-242. ISSN 1471-6941.

- ^ David C. Richardson, Meredith A. Holgerson, Matthew J. Farragher, Kathryn M. Hoffman, Katelyn B. Due south. Rex, María B. Alfonso, Mikkel R. Andersen, Kendra Spence Cheruveil, Kristen A. Coleman, Mary Jade Farruggia, Rocio Luz Fernandez, Kelly L. Hondula, Gregorio A. López Moreira Mazacotte, Katherine Paul, Benjamin L. Peierls, Joseph Due south. Rabaey, Steven Sadro, María Laura Sánchez, Robyn L. Smyth & Jon N. Sweetman (2022). "A functional definition to distinguish ponds from lakes and wetlands". Scientific Reports. 12 (one): 10472. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-14569-0. PMC9213426. PMID 35729265.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ a b Clegg, J. (1986). Observer'southward Book of Pond Life. Frederick Warne, London

- ^ Clegg, John, 1909-1998. (1986). The new observer's book of pond life (4th ed.). Harmondsworth: Frederick Warne. ISBN0-7232-3338-1. OCLC 15197655.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors listing (link) - ^ a b c Keddy, Paul A. (2010). Wetland ecology : principles and conservation (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Printing. ISBN978-1-139-22365-2. OCLC 801405617.

- ^ Biggs, Jeremy; Williams, Penny; Whitfield, Mericia; Nicolet, Pascale; Weatherby, Anita (2005). "fifteen years of pond assessment in Britain: results and lessons learned from the work of Pond Conservation". Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems. fifteen (6): 693–714. doi:10.1002/aqc.745. ISSN 1052-7613.

- ^ Hartman, Travis; Tyson, Jeff; Page, Kevin; Stott, Wendylee (2019). "Evaluation of potential sources of sauger Sander canadensis for reintroduction into Lake Erie". Journal of Cracking Lakes Enquiry. 45 (six): 1299–1309. doi:10.1016/j.jglr.2019.09.027. ISSN 0380-1330. S2CID 209565712.

- ^ Adamson, David; Newell, Charles (ane February 2014). "Frequently Asked Questions about Monitored Natural Attenuation in Groundwater". Fort Belvoir, VA. doi:x.21236/ada627131.

- ^ Karki, Jhamak B (1 January 1970). "Koshi Tappu Ramsar Site: Updates on Ramsar Data Sheet on Wetlands". The Initiation. 2 (i): 10–16. doi:ten.3126/init.v2i1.2513. ISSN 2091-0088.

- ^ Céréghino, R.; Biggs, J.; Oertli, B.; Declerck, Southward. (2008). "The ecology of European ponds: defining the characteristics of a neglected freshwater habitat". Hydrobiologia. 597 (1): 1–half-dozen. doi:10.1007/s10750-007-9225-8. ISSN 0018-8158. S2CID 30857970.

- ^ "Newton of Braintree, Baron, (Antony Harold Newton) (1937–25 March 2012)", Who Was Who, Oxford University Press, 1 Dec 2007, doi:10.1093/ww/9780199540884.013.u29423, retrieved sixteen Nov 2020

- ^ Swimming, Edward (d 1629). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. 28 November 2017. doi:10.1093/odnb/9780192683120.013.22489.

- ^ Davis, Craig A.; Smith, Loren Yard.; Conway, Warren C. (2005). "Lipid Reserves of Migrant Shorebirds During Spring in Playas of the Southern Peachy Plains". The Condor. 107 (two): 457. doi:ten.1650/7584. ISSN 0010-5422. S2CID 85609044.

- ^ Brönmark, Christer; Hansson, Lars-Anders (21 December 2017). "The Biology of Lakes and Ponds". Oxford Scholarship Online. Biology of Habitats Series. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198713593.001.0001. ISBN978-0-xix-871359-iii.

- ^ Northern prairie wetlands. Valk, Arnoud van der., National Wetlands Technical Quango (U.S.) (1st ed.). Ames: Iowa Land University. 1989. ISBN0-8138-0037-4. OCLC 17842267.

{{cite volume}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Kettles (U.Due south. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov . Retrieved xvi November 2020.

- ^ "How exercise glaciers affect country? | National Snow and Water ice Information Center". nsidc.org . Retrieved 16 Nov 2020.

- ^ a b c d eastward f Johnson, Pieter T. J.; Preston, Daniel L.; Hoverman, Jason T.; Richgels, Katherine L. D. (2013). "Biodiversity decreases affliction through anticipated changes in host community competence". Nature. 494 (7436): 230–233. Bibcode:2013Natur.494..230J. doi:ten.1038/nature11883. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 23407539. S2CID 205232648.

- ^ Bagenal, T. B.; Lowe-McConnell, R. H. (1976). "Fish Communities in Tropical Freshwaters: Their Distribution, Ecology and Evolution". The Journal of Animal Environmental. 45 (2): 616. doi:x.2307/3911. ISSN 0021-8790. JSTOR 3911.

- ^ a b Keddy, Paul A. (2010), "Conservation and management", Wetland Ecology, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 390–426, doi:10.1017/cbo9780511778179.016, ISBN978-0-511-77817-9 , retrieved 16 November 2020

- ^ Cutko, Andrew; Rawinski, Thomas (13 August 2007), "Flora of Northeastern Vernal Pools", Science and Conservation of Vernal Pools in Northeastern North America, CRC Press, pp. 71–104, doi:ten.1201/9781420005394.sec2, ISBN978-0-8493-3675-1 , retrieved 16 November 2020

- ^ "Toward Ecosystem Restoration", Everglades, CRC Press, pp. 797–824, i Jan 1994, doi:10.1201/9781466571754-41, ISBN978-0-429-10199-1 , retrieved 16 Nov 2020

- ^ "Freshwater ecosystems". Forest Research. 29 May 2018. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ^ "Why are ponds important?". Ghost Ponds : Resurrecting lost ponds and species to assist aquatic biodiversity conservation. xxx Dec 2013. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ^ "Why Ponds are Of import to the Surround (How you lot can assist)". Pond Informer. 31 December 2018. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ^ Birx-Raybuck, Devynn A.; Price, Steven J.; Dorcas, Michael E. (21 November 2009). "Pond age and riparian zone proximity influence anuran occupancy of urban memory ponds". Urban Ecosystems. thirteen (2): 181–190. doi:10.1007/s11252-009-0116-9. ISSN 1083-8155. S2CID 3118057.

- ^ "Water Chemistry Testing". world wide web.ponds.org . Retrieved xvi Nov 2020.

- ^ Zongo, Bilassé; Zongo, Frédéric; Toguyeni, Aboubacar; Boussim, Joseph I. (one February 2017). "H2o quality in woods and hamlet ponds in Burkina Faso (western Africa)". Journal of Forestry Research. 28 (5): 1039–1048. doi:10.1007/s11676-017-0369-8. ISSN 1007-662X. S2CID 42654869.

- ^ "Regional Perspectives : Local Traditions", Continuum Companion to Hindu Studies, Bloomsbury Bookish, 2011, doi:10.5040/9781472549419.ch-006, ISBN978-i-4411-0334-5 , retrieved sixteen November 2020

- ^ Traditional Ponds – The Water Urban-ism of Newar Civilization Archived 2021-03-22 at the Wayback Car past Padma Sunder Joshi, Spaces Nepal, April 2018, retrieved 11 October 2019

- ^ Boothby, John (1999). "Framing a Strategy for Pond Mural Conservation: aims, objectives and issues". Landscape Research. 24:1: 67–83. doi:x.1080/01426399908706551 – via Taylor & Francis Online.

- ^ Colina, Matthew J.; et al. (2018). "New policy directions for global pond conservation". Conservation Letters. 11 (five): e12447. doi:10.1111/conl.12447. S2CID 55293639 – via Wiley.

- ^ Encyclopedia of inland waters. Likens, Gene East., 1935-. [Amsterdam]. xix March 2009. ISBN978-0-12-370626-3. OCLC 351296306.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Ridgwell, A.; Edwards, U. (2007), "Geological carbon sinks.", Greenhouse gas sinks, Wallingford: CABI, pp. 74–97, CiteSeerXten.1.1.371.7116, doi:10.1079/9781845931896.0074, ISBN978-1-84593-189-6 , retrieved sixteen November 2020

- ^ Reay, D. S.; Grace, J. (2007), "Carbon dioxide: importance, sources and sinks.", Greenhouse gas sinks, Wallingford: CABI, pp. 1–10, doi:ten.1079/9781845931896.0001, ISBN978-i-84593-189-6 , retrieved sixteen November 2020

- ^ Burke, Ty (21 May 2019). "Farm Ponds Sequester Greenhouse Gases". Eos. 100. doi:10.1029/2019EO124083. ISSN 2324-9250.

- ^ a b Radosevich, Steven R. (2007). Ecology of weeds and invasive plants : relationship to agronomics and natural resource management. Holt, Jodie S., Ghersa, Claudio., Radosevich, Steven R. (3rd ed.). Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley-Interscience. ISBN978-0-470-16894-iii. OCLC 181348071.

- ^ Genet, John A.; Olsen, Anthony R. (2008). "Assessing depressional wetland quantity and quality using a probabilistic sampling blueprint in the Redwood River watershed, Minnesota, United states". Wetlands. 28 (2): 324–335. doi:x.1672/06-150.1. ISSN 0277-5212. S2CID 29365811.

- ^ a b Dufour, Simon; Piégay, Hervé (2005), "Restoring Floodplain Forests", Forest Restoration in Landscapes, New York: Springer-Verlag, pp. 306–312, doi:10.1007/0-387-29112-1_44, ISBN0-387-25525-7 , retrieved sixteen November 2020

- ^ Geist, Juergen; Hawkins, Stephen J. (31 August 2016). "Habitat recovery and restoration in aquatic ecosystems: current progress and future challenges". Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems. 26 (5): 942–962. doi:10.1002/aqc.2702. ISSN 1052-7613.

Further reading [edit]

- Hughes, F.M.R. (ed.). (2003). The Flooded Wood: Guidance for policy makers and river managers in Europe on the restoration of floodplain forests. FLOBAR2, Department of Geography, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK. 96 p.[1]

- Surroundings Canada. (2004). How Much Habitat is Enough? A Framework for Guiding Habitat Rehabilitation in Great Lakes Areas of Concern. 2d ed. 81 p.[ii]

- Herda DJ (2008) Zen & the Art of Swimming Building Sterling Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-4027-4274-3.

- W.H. MacKenzie and J.R. Moran (2004). Wetlands of British Columbia: A Guide to Identification. Ministry building of Forests, Land Direction Handbook 52.

![]()

Wikiquote has quotations related to Pond .

Are Ponds Freshwater Or Saltwater,

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pond

Posted by: kongnoestringthe.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Are Ponds Freshwater Or Saltwater"

Post a Comment